A1c tests are more likely to produce inaccurate results for Black patients. Why? Because hemoglobin variants are more common in people with African, South and Southeast Asian, and Mediterranean ancestry.

History of A1c Guidelines in the U.S.

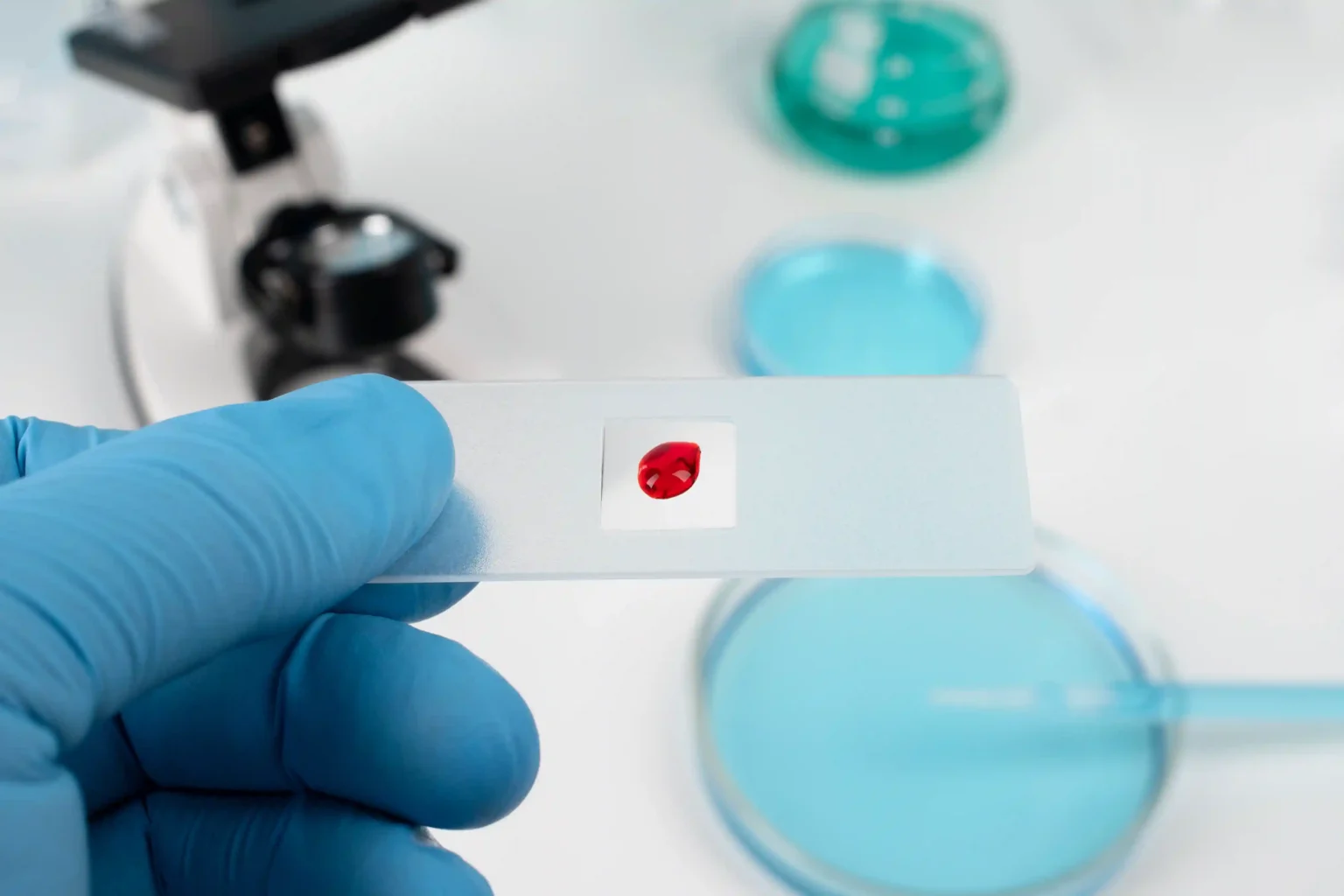

Since the 1980s, A1c guidelines have been used to measure blood sugar levels and gauge the risk of developing diabetes and diabetes-related complications.

However, U.S. medical research has failed to draw diverse patient pools for research trials. Minority populations have historically been excluded from or had less access to trial participation. As a result, “A1c guidelines were created based on data that disproportionately studied white people,” says Julia Sclafani.

Despite more recent studies of A1c, including more diversity among racial and ethnic groups, the overall guidelines continue to be racially biased, skewing the accuracy of test results.

Observing these results, professionals must question and determine how many people have had their A1c readings misinterpreted based on data that didn’t account for their genetic makeup. Why? To prevent mistreatment and underdiagnosis of diabetes in all people.

How do hemoglobin variants and genetics affect A1c levels?

We inherit the type of hemoglobin in our blood from our genetic parents, the most common being hemoglobin A. However, many other variants can affect A1c levels, most common in those with African, South and Southeast Asian, and Mediterranean ancestors.

Hemoglobin variants do not affect patients’ risk for diabetes, but they can affect patients’ A1c levels. So, if patients have a hemoglobin variant, a regular A1c test will not be a good indicator for their diabetes management and treatment plans.

How can we work toward better health equality?

We must work toward better representation in clinical trials to reflect better testing efficacy, treatment guidelines, and standards of care.

For that to happen, professionals must ensure that the clinical trials are easily accessible to all racial and ethnic participants. There are many barriers to accessing clinical trials, including the study location being accessible via public transportation, lengthy time commitments (requiring a work schedule or workplace policy that accommodates these appointments, and having support at home, such as childcare), and more. Professionals can do better in creating opportunities for all to participate in clinical trials by making the location, testing times, and commitment length more manageable.

If the U.S. does not ensure the quality and diversity of clinical trials, the patient pools will not represent the national population. This can mean a “mismatch in documented drug dosage effects and outcomes based on the research and efficacy in the general population.”

In addition to this improvement, the U.S. market must introduce A1c measurement devices free from hemoglobin variant interference to overcome racial bias and produce accurate results. This solution would mean accurate HbA1c results for all patients, regardless of race and ethnicity.

Currently, there are no A1c measurement device options available in the U.S. that consider hemoglobin variants. However, Orange Biomed aims to be the first to provide that solution. Orange Biomed is currently conducting trials in Korea, planning U.S. trials, and seeking FDA clearance.

Follow Orange Biomed on Linkedin, Instagram, and Facebook to learn more about our solution to making diabetes management more accessible.

Source :